The previous post in this series introduced the different languages used to write magical texts in Egypt from the second to twelfth centuries CE – Demotic, Greek, Coptic – and discussed their changing usage. In the second and third centuries most magical texts were written in Greek or Demotic, while Greek alone dominated in the fourth century. Greek was then replaced by Coptic from the fifth century, and Coptic itself began to decline in the tenth, as Egyptians increasingly began to speak and write Arabic instead of Coptic. But throughout this period, many Egyptians would have been able to speak, and even read, more than one language, and this is especially true of transitional moments, when two or more written languages were being regularly used at the same time.

One way in which interaction between languages is visible is in loanwords – words borrowed from one language into another. English has a huge number of loanwords – approximately 70% of the words in a modern dictionary will be borrowed from other languages, mainly French, Latin, and Greek. Many of these are specialised terms, however, and the majority of the words which we regularly use are from Old English roots. Coptic too has many loanwords, primarily from Greek, constituting about 40% of the total vocabulary according to some estimates. But, as in English, the most commonly used words are not generally loanwords, but from native, in this case Egyptian, roots. Coptic magical texts, like all other genres, regularly use loanwords. Invocations frequently begin by summoning divine beings with phrases such as “I call upon you”, and two of the words commonly used for “call upon”, epikali and parakali, are borrowed from Greek (a third word, ōš, comes from a native Egyptian root). As mentioned in an earlier post, from approximately the ninth century onwards, we also begin to see a lot of Arabic words borrowed into Coptic magical texts, usually for ingredients to be used in offerings; one example from a love spell lists cotton, tar, the gall of the silurus-fish, and white pepper. The word used for cotton, qutun, is Arabic, while the word used for pepper, piper, is from Latin via Greek (incidentally, you can see that we use these same loanwords in English).

Image property of the Special Collections Research Center, University of Michigan Library.

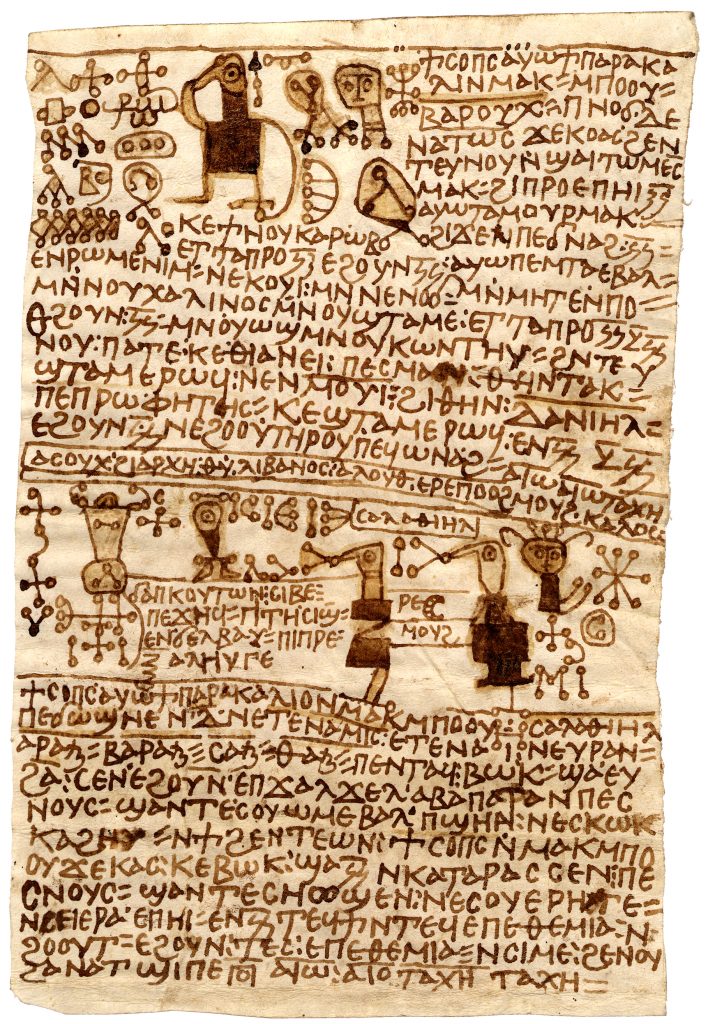

We also find more dramatic examples of interaction between languages. Among the nearly 900 magical manuscripts from Egypt contained in our database, 34, dating to between the third and twelfth centuries, contain texts in both Coptic and Greek. We’ve already discussed one of the earliest and most complex of these, PGM IV, in some detail – 72-pages long, it is written mainly in Greek, but with a few very interesting texts in Old Coptic. Another example, probably from later in the same century, provides us with different phenomenon. Michigan Ms. 136 is a 16-page codex purchased in the Faiyum, the oasis to the west of the Nile Valley, and contains 32 recipes, most for healing, copied by four different scribes. It begins with instructions for creating an amulet in Coptic, before shifting to a series of instructions in Greek for treating gout, and then continuing with a Greek invocation to the Egyptian goddess Isis to heal a gynaecological problem. Most of the remaining 29 recipes are in Coptic, but there are a few exceptions, including a verse from Homer’s Iliad, which is to be copied onto an amulet to treat fever.

This last example gives us a hint as to why texts in different languages might be mixed together. Even in predominantly monolingual English-speaking countries, we often know a few songs and poems in other languages – examples include the French nursery rhyme Frère Jacques, and pop songs which manage to cross linguistic barriers, such as the German 99 Luftballons and Du hast in the 1980s and 1990s. While translated English-language versions of these songs often exist, even monolingual English speakers generally prefer the original French or German versions, which they might be able to sing, but not completely understand, and we could easily imagine a book of songs or nursery rhymes which included a mix of both English and non-English examples. We often have evidence that scribes didn’t completely understand the texts in the different languages they copied – the Greek invocation to Isis, for example, has several spelling mistakes which suggest that, like an English-speaking child learning Frère Jacques, they might know the sounds they were supposed to recite, but not exactly how to spell the words, or what they meant.

Image from Schulz and Kolta (1998).

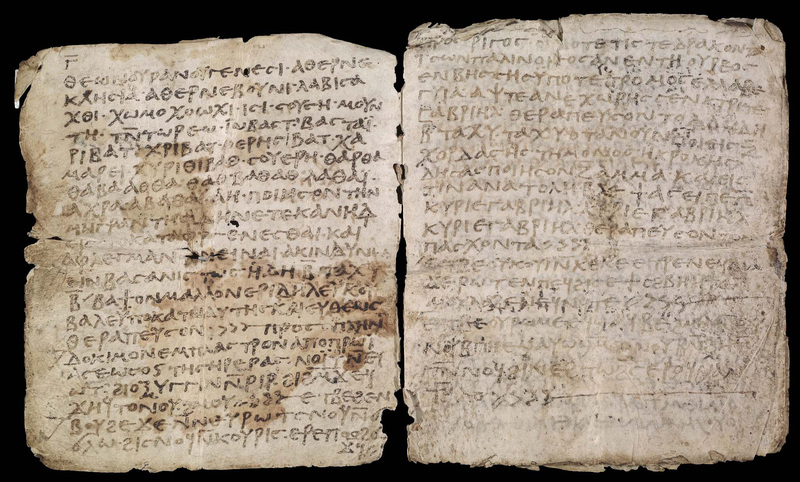

The Michigan codex gives us a case of a magical practitioner drawing together texts from different traditions – Greek invocations and epic poetry, Coptic charms and medical recipes – but our second example is more systematic. P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 500 + 501 is one of the 25 magical manuscripts from our database which mix together Coptic and Arabic texts. These manuscripts date from the 7th century, after the Arab conquest of Egypt, to the 20th century, from which we have an example of a bilingual amulet created to heal a scorpion sting copied in 1932.

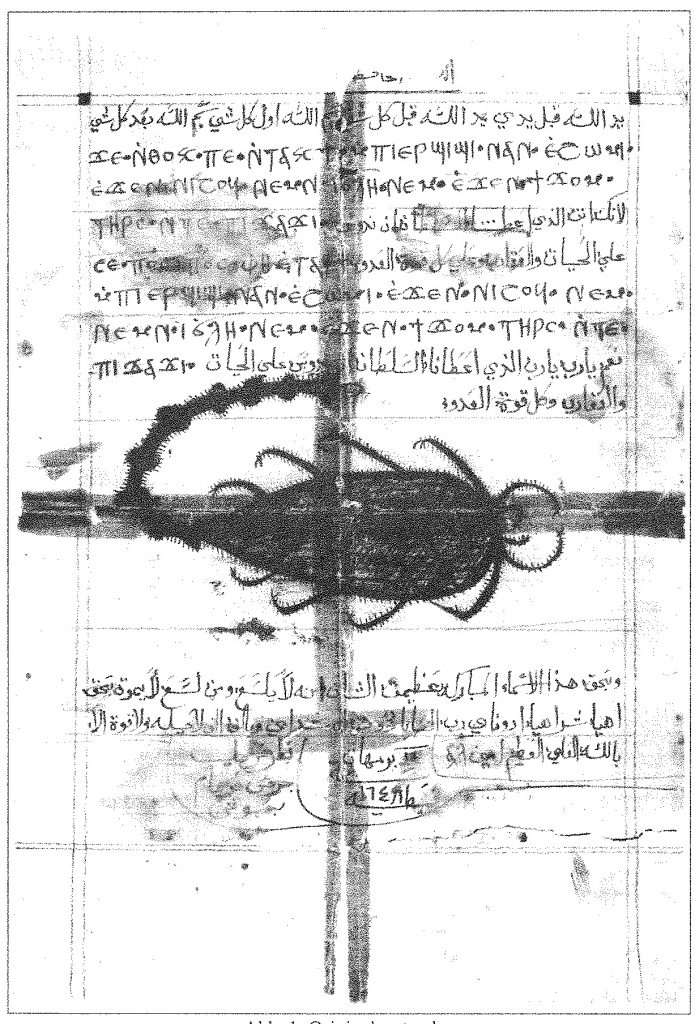

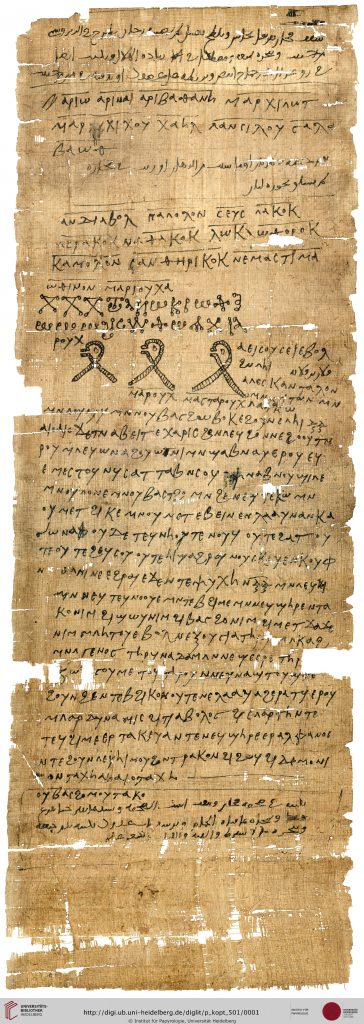

P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 500 + 501 is a long rotulus (a vertical roll), written on both sides, containing 8 recipes for manipulating relationships – love spells to bring people together, separation spells to tear them apart, curses to harm them, and favour spells to bring them luck. Each of the recipes is accompanied by an illustration, which is supposed to be copied onto an object as part of the spell. In each case, the invocations are written in Coptic, while the ritual instructions are in Arabic. For example, one of the spells is a particularly nasty curse written in Coptic:

Scandal and destruction and strife went into the house of so-and-so! Yea, yea, take the grace from his face for all the days of his life, so that everyone who sees him will hate him, and anyone who sees him should hate him and pass him by! Give him shame and suffering and hatefulness and imprisonment and hunger and poverty with no property! Leave him neither livestock nor gold nor silver, nor clothes nor house down to the smallest thing! Bring down upon the soul of so-and-so and his house and his livestock, and his wife, and his children all devastation and all strife and all enmity, before all the powers of the earth and the whole race of Adam and daughters of Eve, so that they all hate him, that they are no longer be able to look upon his image, neither shall any stand beside him except (an evil) Power and the Devil and (the Devil’s daughter) Sparte, and his wife shall be destroyed and his children shall be orphaned, and the inside of his house shall fill with serpents, snakes and demons! Quickly, quickly, yea, quickly!

P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 500 + 501 ll.58-79

To use this, the owner of the manuscript would need to be able to read Coptic, but the following instructions are written in Arabic:

You write (the diagram) on a pottery bowl, recite (the spell) over the back of the ostracon and bind it to an empty well, and … erase (the diagram) with the crop milk of a pigeon, and hide it at the door of your enemy. You write it with menstrual blood and burn it with styrax, galbanum, frankincense and sheep hair.

P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 500 + 501 ll.81-83

The ritual instructions are very similar to those that we find in earlier, purely Coptic, rituals, and so it’s quite possible that at some stage they were translated from Coptic into Arabic. The simplest explanation for this is that at the time this text was copied, perhaps around the ninth century, the person who wanted to use it was more used to reading and speaking Arabic, but, like an English speaker who learns Frère Jacques in French, they wanted to keep the sounds, rhythm, and in this case, magical power, of the text in its original language.

Mixed-language texts make studying Egyptian magic more complicated – it is difficult enough to master one ancient language, let alone two or more, but understanding them is vital for understanding the way in which people and texts could crossed cultural and linguistic barriers. In a multilingual society, there are always meanings behind the languages we think, write, read, and speak in, even if we are not aware of them.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Bilabel, Friedrich, and Adolf Grohmann. Griechische, koptische und arabische Texte zur Religion und religiösen Literatur in Ägyptens Spätzeit, Heidelberg: Verlag der Universitätsbibliothek, 1934, no. 140, p. 405-408.

The original publication of O.Heid. Inv. Kopt. 683, the text with Greek and Arabic loanwords shown at the beginning of this post (pages 405-408, no.140), and inv. 500 + 501 (pages 328-344, no. 123).

Grossman, Eitan. “Greek Loanwords in Coptic”. In Encyclopedia of Ancient Greek Language and Linguistics, edited by Georgios K. Giannakis et al. Leiden: Brill, 2014: 118-120.

A discussion of Greek loanwords in Coptic.

Meyer, Marvin W., and Richard Smith. Ancient Christian Magic: Coptic Texts of Ritual Power. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press, 1999, no. 43, p. 83-90.

Contains an English-language translation of Michigan Ms. 136.

Richter, Tonio Sebastian. “Coptic [, Arabic loanwords in].” In Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics, vol. I, edited by K. Versteegh. Leiden : Brill, 2006: 595-601.

A discussion of Arabic loanwords in Coptic.

Schulz, Regine and Kamal Sabri Kolta, “Schlangen, Skorpione und feindliche Mächte”. In Biblische Notizen. Beiträge zur exegetischen Diskussion 93 (1998): 89-104

Contains the publication of the bilingual Coptic-Arabic amulet written in 1932.

Worrell, W. H. “Coptic Magical and Medical Texts.” Orientalia, NOVA SERIES n°4 (1935): 17–37.

The original edition of Michigan Ms. 136.