This post is the fourth in a mini-series about bilingual recipes in Egyptian and Greek from the 3rd/4th century papyrus codex PGM IV (Greek Magical Papyrus 4) – the “Bilingual Exorcism” (PGM IV. 1227-1264). This practice is written upon pages 28 and 29 of the codex and departs considerably from the other practices in this mini-series because it seems to derive from a Judaeo-Christian, rather than Pharaonic or Graeco-Egyptian, cultural context.

This composite recipe features ritual instructions and invocations in the Greek language, as well as one section written in the Egyptian-Coptic language that makes use of an innovative Old Coptic script. Unlike the other Egyptian-Coptic language sections of the codex, it is principally the Greek script, with only the letter kjima (ϭ) derived from demotic. Because of all the other bilingual practices in this codex, there is no doubt that the owner of this codex was an Egyptian-Greek bilingual and was presumably able to read various different Old Coptic scripts, such as those seen in the previous posts in this series. However, this text was almost certainly copied from another manuscript, and suggesting that there were Egyptian-Coptic language texts that were also written in only the Greek script, in addition to those which used Old Coptic scripts. This would itself then suggest that someone literate in the Greek script, but not in demotic or (Old) Coptic, would have been able to vocalise the sounds of the Egyptian-Coptic text, just as, say, a modern anglophone might transliterate an Arabic text into Latin script.

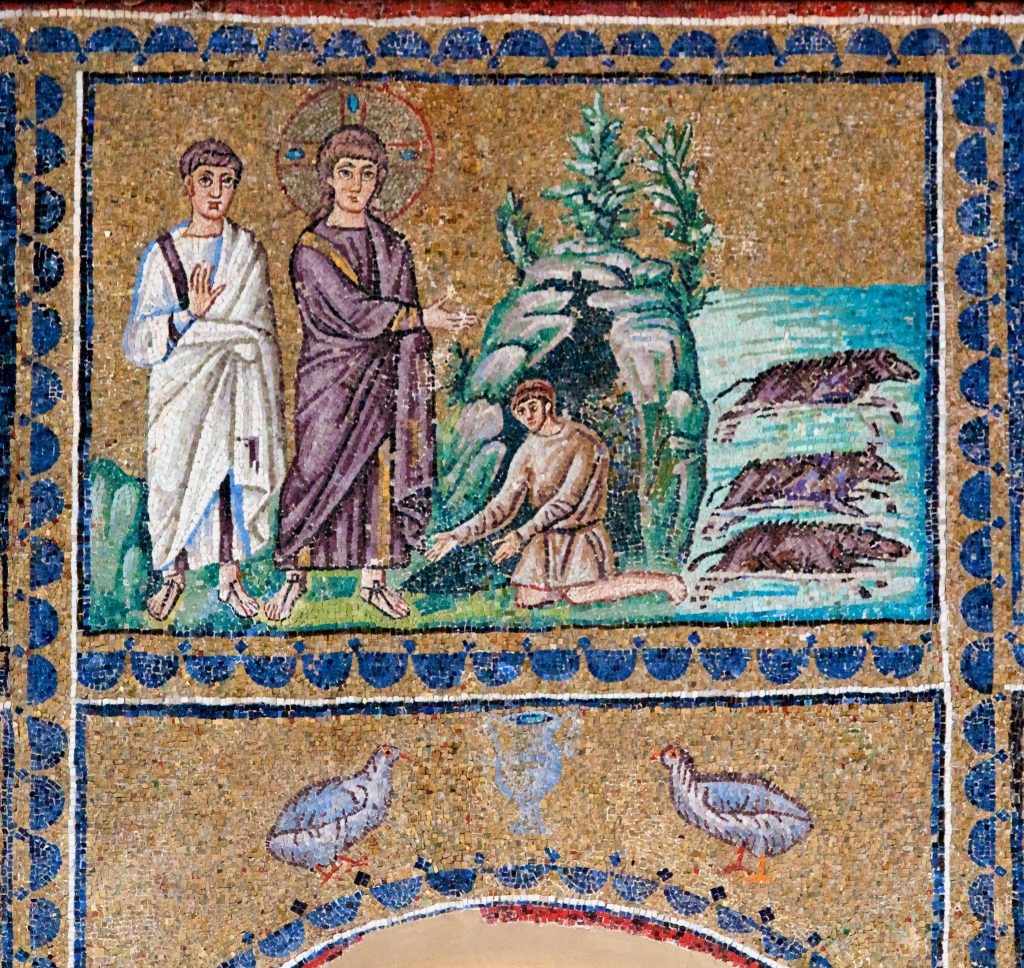

The practice is titled an “excellent method to cast out demons” and instructs, in Greek, that a formula is to be spoken over the head of the possessed person. First and foremost, the practitioner must place olive branches before that person, six of which are later specified to be tied into loops, the seventh is to be used as a whip as the invocations are recited. Then the practitioner must stand before the possessed person and recite the following invocation in Egyptian-Coptic (1231-1235):

“Hail God of Abraham! Hail God of Isaac! Hail God of Jacob! Jesus the Khrēstos, the Holy Spirit, Son of the Father, who is in the upper-part of the seven and who is in the inner-part of the seven: Bring Iaō Sabaōth!

Let your (pl.) power emanate from so-and-so, until you case out this one, the unclean demon, Satan, who is in him.”

The invocations then continue in Greek (1235-1248):

“I adjure you, demon, whoever you are, by this god: Sabarbarbathiōth Sabarbarbathiouth Sabarbarbathiōnēth Sabarbarbarphai.

Come out demon, whoever you are, and stay away from so-and-so. Now, now, quickly, quickly!

Come out demon, since I bind you in unbreakable adamantine chains, and I cast you into the black chaos in destruction!”

Instructions for a phylactery, a protective amulet, are also included as part of this composite practice, which the text specifies must be worn by the freshly exorcised individual as soon as the demon has been cast out. The following magical names are to be written upon a piece of tin (1252-1264):

“Bōr Phōr Phor Ba Phor Phor Ba. Bes Charin Baubōte Phōr Bōrphorba Phorbabor Baphorba Phab- raiē Phōrba Pharba Phōrphōr Phorba Bōphor Phorba Phorphor Phorba Bōborborba Pamphorba Phōrphōr Phōrba. Guard so-and-so.”

In case this phylactery is not efficacious enough, a variant is included, bearing a particular character, or magical symbol. This character can be seen in the image below, the last item on the last line before the large space left on page 29.

In all, this practice includes three sections of invocations that command the demon to “come out” from the possessed person. The first, in Egyptian-Coptic, invokes the three Hebrew Patriarchs, followed by Jesus and a Trinitarian formula, mentioning Father, Son and Holy Spirit. The second commands Iaō Sabaōth, one of the titles of the Hebrew god, to be brought. This is before commanding the plural “powers” – likely the previously invoked Patriarchs, Jesus, and the Holy Trinity – to cast out the demon, which is termed “Satan”! Edward Love’s recent study of this recipe summarised the work of Martin Rist, who highlighted that Origen, writing in the middle of the 3rd century CE, stated the names of the Patriarchs and God were understood to have such power that they were widely employed in both exorcisms and prayers in Jewish communities. Unsurprisingly, this tripartite invocation became used not only in Graeco-Egyptian magical practices, but across the entire Eastern Mediterranean, and not only in exorcisms, but also practices for all manner of favourable outcomes. The third part of the invocation commands the demon to “come out” once again, ensuring that the demon will be bound in “unbreakable adamantine chains” and delivered “into the black chaos in destruction”. Utilising the language of defixiones, curse texts conventionally inscribed upon lead tablets and deposited, the practice has been inverted – a demon is to be taken away from, rather than brought to, an individual.

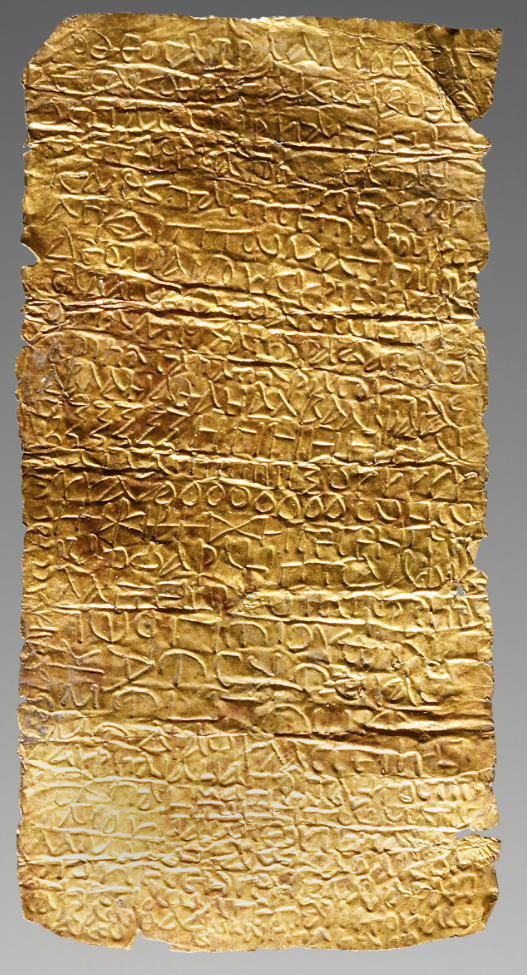

A most interesting parallel is that now housed in the J. Paul Getty Museum, edited by Roy Kotansky (1980). This 3rd century CE gold lamella, of unknown provenance, was once rolled and inserted into a cylindrical case, presumably to have been worn around the neck of the possessed person. The exorcism beings with the invocation of “the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” and acts against “every evil spirit” as well as “every epileptic fit and seizure”.

The practice of invoking the God of the Patriarchs was also transmitted into the Coptic magical tradition, with a 4th-5th century CE curse on papyrus now housed in the Bodleian library invoking the “God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob” alongside ten angelic names, Abrasax, and the Holy Trinity, to strike down three individuals who had been accused of wronging the client.

Another distinguishing feature, noted in the translation above, is the invocation of the khrēstos, “the Excellent”, as opposed to the khristos, “the Anointed”, or the “Christ” – the conventional epithet of Jesus. Although khrēstos may simply have been a misspelling for, and was probably pronounced the same as, khristos, Bentley Layton (1979) has noted that in the “Treatise on Resurrection” preserved in the 4th century CE Nag Hammadi Codex I, the spelling is also khrēstos, i.e. “the Excellent”, and this spelling is used in many other contexts, in both Greek and Coptic. Since the two seem to have been homophones, it is unclear whether there was any deliberate attempt to distinguish Jesus from the Messianic “anointed one” in this text. This seems unlikely, after all, given that both “the Holy Spirit” and “Son of the Father” are invoked shortly afterwards.

“Jesus the Khrēstos”, “the Holy Spirit”, and “Son of the Father” are all described in the text as being “in the upper-part of the seven” and “in the inner-part of the seven”. This “seven” is the heavens, and the invocation of the “seven heavens” is paralleled in many exorcisms. One example, also published by Kotansky (1995), features a liturgical exorcism whose text adjures Iaō “by the seven heavens, the two archangels, and the great name Cherubim” to “save the bearer” of the gemstone upon which it is inscribed. This blue chalcedony stone, patinated white, was discovered in Asia Minor, and is now in a private collection. As a result, this rare example suggests that such practices had a wide dissemination throughout Egypt and across the Eastern Mediterranean.

Much has been written, discussed, and debated about the development of exorcisms of this form among Jewish communities during the early centuries of the 1st millennium BCE, some of which was discussed recently with respect to this text by Love (2016: §6.4). From the Jewish communities in which they developed, the exorcism of demons became a widespread practice in Christian communities too, and both textual traditions of course influenced Coptic magic for centuries to come, resulting in numerous attestations of exorcisms among the Coptic magical papyri studied by our project. This bilingual example from PGM IV, then, evidences a nexus between many pre-Christian traditions preserved among the Graeco-Egyptian magical papyri and the subsequent Christian traditions that developed and persevered in Byzantine and Islamic Egypt, and even up until today.

In September 2012, Omar Rahman authored an article describing mass exorcisms by Father Sama’an, a Coptic priest, in Cairo. The St. Sama’an Church, built inside a massive cave on Mount Muqattem, can seat up to 20,000 people, which both Christians and Muslims attend in order to have their demons cast out. One witness describes a practice which at least in part parallels the text we have discussed in this post, that “[w]hen the priest mentions the name of Jesus, the devil is destroyed”. From one textual witness in the Roman Period to one oral witness in the modern day, the efficacy of the names of Jesus in exorcisms in Egypt can therefore be said to have a history stretching back at least 1,700 years!

Bibliography and Further Reading

For the most recent study of this recipe, and bibliography of past treatments, see Chapter 6 of: Love, Edward O. D. Code-Switching with the Gods: The Bilingual (Old Coptic-Greek) Spells of PGM IV (P. Bibliothèque nationale supplement Grec. 574) and their Linguistic, Religious, and Socio-cultural Context in Late Roman Egypt. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016. URL

Kotansky, Roy. “Two Amulets in the Getty Museum: A Gold Amulet for Aurelia’s Epilepsy: An Inscribed Magical-Stone for Fever, “Chills,” and Headache.” The Getty Museum Journal 8 (1980): 181-188.

Kotansky, Roy. “Remnants of a Liturgical Exorcism on a Gem.” Muséon 108 (1995): 143-156.

Layton, Bentley. The Gnostic Treatise on Resurrection from Nag Hammadi, 1979.

Rahman, Omar H., 2012, “Mass Exorcisms in Cairo” https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/dp4jaw/mass-exorcism-in-cairo

Rist, Martin. “The God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob: A Litrugical and Magical Formula.” Journal of Biblical Literature 57: 3 (1938): 289-303.

One Comment

Pingback: