Once we have defined magical texts, the next thing we need to do is categorise them. This week we’ll discuss one of the major divisions we use to classify magical papyri – their separation into formularies and applied texts.

The distinction is fairly simple: formularies – also called handbooks or grimoires – contain one or more recipes for performing rituals. By contrast, applied or activated texts are objects – such as amulets or curse tablets – created in the course of these magical rituals.

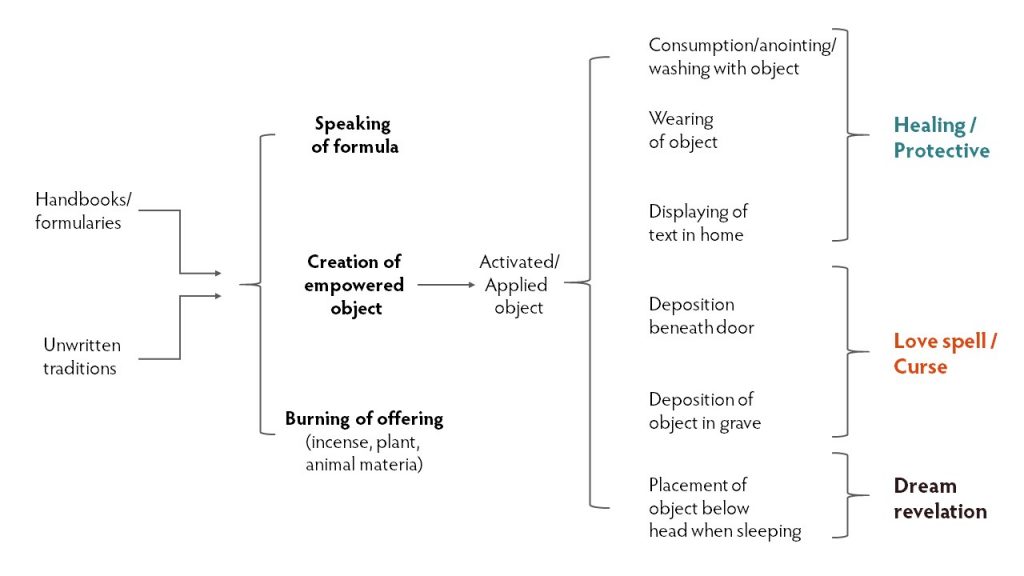

One way of understanding this distinction is by thinking about the process of performing a ritual. Before an individual could carried out a magical ritual, they needed to know how to perform it. There are two primary ways that they might gain this knowledge – the first is by learning it from another practitioner, something that almost certainly happened, but which would leave no archaeological trace. The second is by reading a recipe in a formulary. This is something of a simplification, of course, since individuals could also have invented their own rituals, perhaps by adapting others that they knew of, and in many cases it seems that some training would have been necessary to fully understand formularies.

While the rituals in the Coptic magical papyri are as diverse as the texts themselves, we can describe a typical or “ideal” ritual as having three parts, probably carried out simultaneously – the speaking of a formula (“spell”), the burning of an offering (usually some type of fragrant resin, such as myrrh, storax or frankincense), and the creation of an empowered object. Through the ritual process, this object was believed to take on divine power, which is sometimes described in terms of an angel or other divine being descending upon it. This object could take many forms – a liquid, such as oil or water, a stone, or a text on papyrus, parchment or metal. The use of this object would then determine the ritual’s outcome – for healing or protection rituals the individual might be washed or anointed with the liquid, or wear an amulet in the form of a inscribed stone or text. In curses or love spells the text might be buried in a grave, so that the spirits of the dead would carry out its goal, or deposited under the victim’s doorway.

We can see, therefore, that while formularies and applied texts might look similar, since the applied texts were usually copied from formularies, they are, in fact, very different types of artefacts. Formularies are technical documents, containing the instructions for the performance of rituals, whereas applied texts are empowered objects containing the divine force of the ritual in which they were created. Nonetheless, the fact that they can look so similar means that it is often difficult to tell them apart. Our database contains 181 manuscripts which we classify as formularies containing Coptic-language texts, while 187 are defined as applied texts. Another 132, though, are defined as “Unclear”, unclassifiable as either formularies or applied texts, while 99 applied texts and 45 formularies have a question mark afterwards, to indicate that their classification is likely but uncertain.

To an extent this is because we are trying to be very cautious at this stage, and define clear criteria – textual and material – for both formularies and applied texts. Formularies, for example, often contain more than one recipe, which frequently each have their own titles, such as “For causing separation”. These recipes contain not only formulae, but also instructions about which incense to burn, when the ritual should be carried out, or which other ritual actions to perform. When the names of individuals are to be inserted when the formulae are spoken or written, they usually have a generic name marker, translated into English as “so-and-so son/daughter of so-and-so”, or “NN son/daughter of NN”.

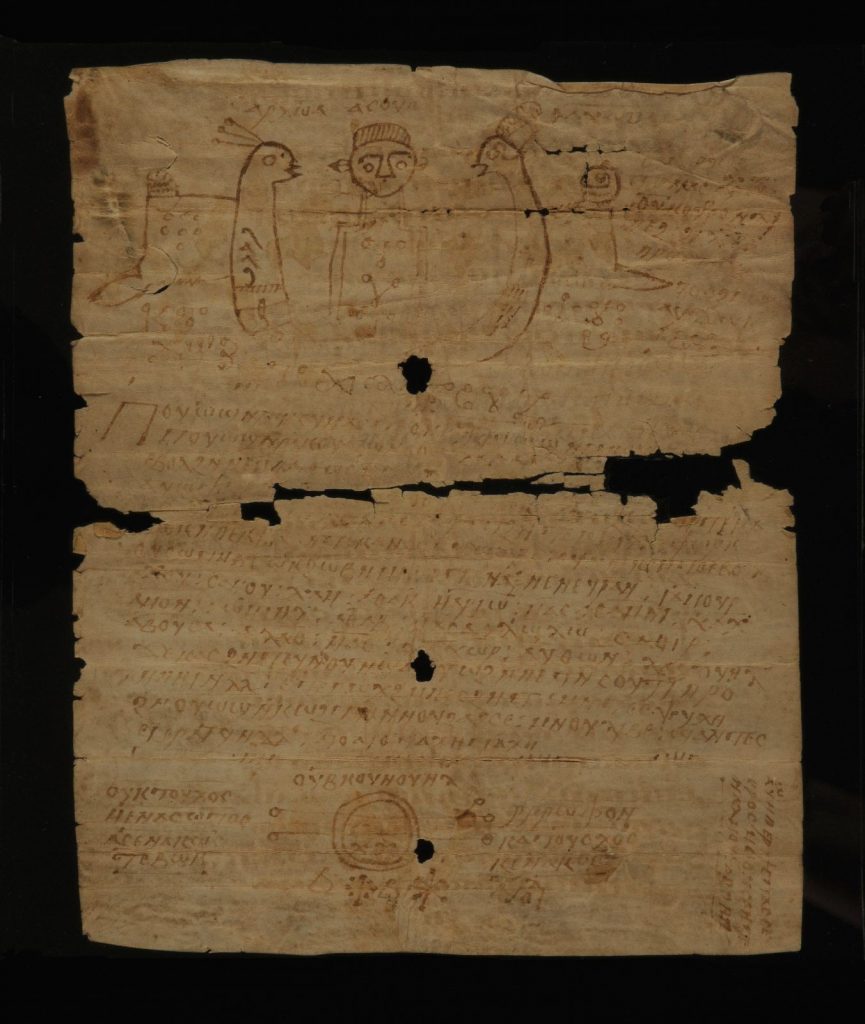

Applied texts, by contrast, will usually contain only formulae, sometimes alongside images and magical signs. The generic name marker is usually replaced with the name of the individual and their mother: “Jacob son of Euphemia”, for example. Applied texts, because they were worn or deposited, are often folded several times, and so extensive folding may serve as another suggestion that an object is an applied text.

One very nice example of this division can be seen in two documents which contain almost exactly the same text. Although these examples are Greek, there are similar, though less striking examples known in Coptic.

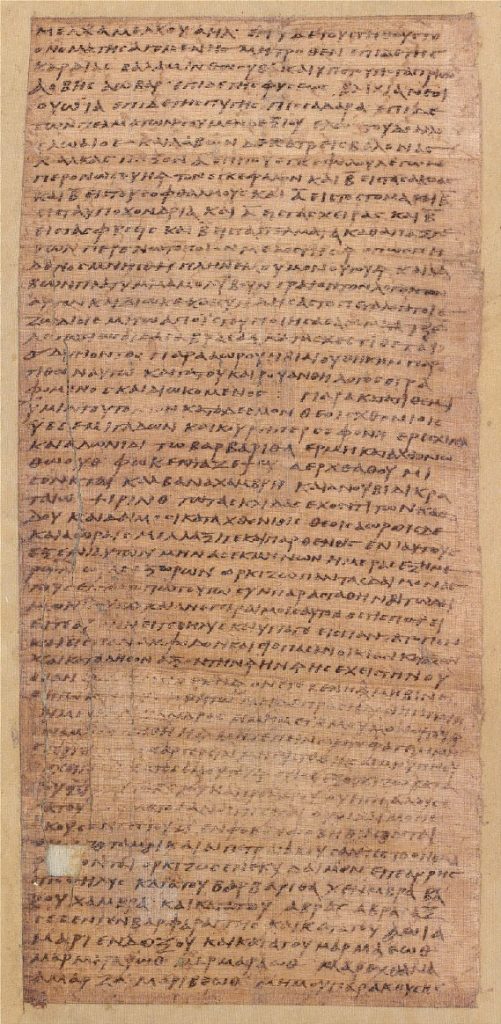

Pages 10-11 (5v-6r) of PGM IV (BNF Suppl. Grec no. 574; 4th century CE, Thebes), the longest surviving magical text from the ancient Graeco-Roman world. These pages contain lines 315-407, containing an elaborate love spell involving the creation of clay figures and a lead curse tablet. [source]

PGM IV is the longest preserved formulary from the ancient world, a 72-page codex containing over 50 recipes in Greek and Coptic for purposes as diverse as causing love, performing divination, cursing, and gathering plants. Although this is the manuscript that many historians have in mind when they imagine a typical magical papyrus, we should note that it is very unusual among surviving texts in terms of its length, and that it comes from a specific time and place – it was probably copied and used in fourth-century CE Thebes, although its recipes certainly have more diverse origins.

Lines 296-466 of this codex contain a “wondrous spell for binding a lover”, one of the most detailed surviving instructions for creating the curse tablets which survive in their hundreds from the ancient Graeco-Roman world. The user is to create two figurines from wax or clay – the war-god Ares and a bound woman being threatened by him with a sword. The woman is to have thirteen needles stuck into her body, and then a formula is to be simultaneously recited and copied onto a lead tablet. The objects and the lead tablet are to be tied together with thread, and buried in the grave of an individual who died violently or before their time. Part of the formula speaks directly to the ghost, referred to as a daimon (“spirit”).

“I adjure all daimons in this place to stand as assistants beside this daimon. Arouse yourself for me, whoever you are, whether male or female… attract her, NN, born of NN”

PGM IV.345-350

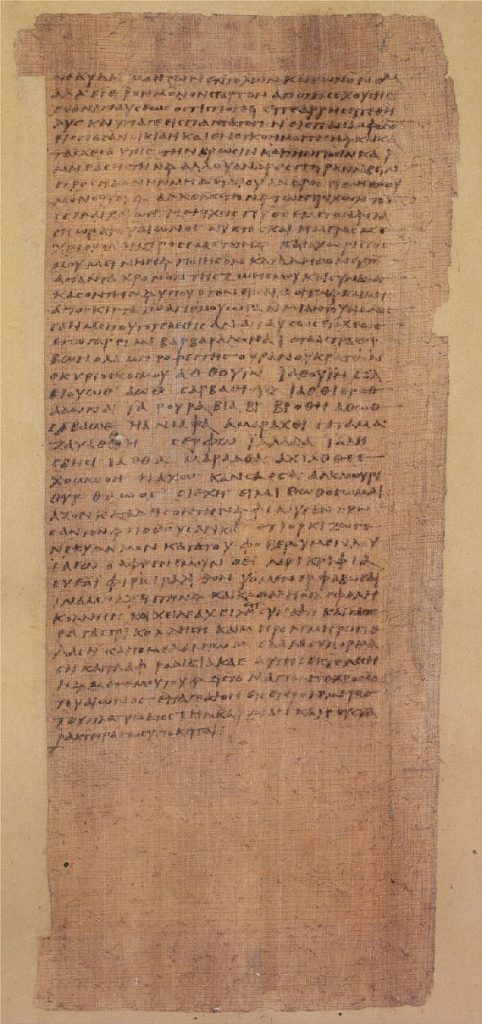

This ritual seems to have been quite popular, since we possess six examples of its formula being used as an applied text, all from second or third century CE Egypt. The most astonishing example is a clay pot found near the city of Antinoopolis, which contained a clay figurine of a woman, pierced by 13 needles in almost the exact fashion described in the formulary, and a lead tablet containing the curse. The parallel passage is as follows:

“I adjure all the daimons in this place to assist this daimon, Antinous. Rouse yourself for me… and bind Ptolemais, born of Aias”

T.Louvre inv. E 27145 ll.5-8

We can see here some obvious changes indicative of its adaptation as an applied text: the generic name marker NN has been replaced by the name of the target of the love spell, Ptolemais, daughter of Aias. The ritualist has even decided to replace the generic daimon with the name of a specific daimon, “Antinous”; scholars disagree as to whether this should be understood as the famous lover of the emperor Hadrian, who died in Egypt in 130 CE and was worshipped as a god in Antinoopolis, the city founded in his honour, or as a less famous dead person named after him. More striking, though, is the way in which the applied objects follow the recipe very closely in some ways while diverging from it in others: the clay woman follows the description in PGM IV almost exactly, yet there is no male figure threatening her. Since the applied version is older than the recipe we have, we may wonder if the recipe it relied on was different, or if the practitioner simply modified the ritual for their own reasons.

Hopefully this digression into Greek-language magic from Egypt shows clearly the differences between formularies and applied texts. In the example here, the formulary is a huge “recipe-book” on papyrus with dozens of different practices, whereas the applied text is a lead tablet, created in the course of a specific ritual and buried in a pot with an ancient “voodoo doll”, yet they both contain versions of the same text, and so can be fruitfully studied together. In the next post in this series, we will discuss some of the problematic cases that cross, or even bring into question, the line between formularies and applied texts.

References and Further Reading

Betz, Hans D. The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation. Including the Demotic Spells. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986. URL

The most accessible translation of PGM IV in English; the love spell discussed here (lines 296-466) appear on pages 44-47.

Brashear, William. “The Greek Magical Papyri: An Introduction and Survey; Annotated Bibliography (1928-1994)”. In Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, vol.2.18.5, edited by Wolfgang Haase. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1995, 3380-3684.

One of the best introductions to and overviews of the Greek magical papyri.

Daniel, Robert W., and Franco Maltomini. Supplementum Magicum (2 vols.). Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1990–1992.

The lead tablet discussed above (T. Louvre inv. E 27145) is edited in volume one of this collection as no. 47.

Faraone, Christopher A. “The Ethnic Origins of a Roman-Era Philtrokatadesmos (PGM IV 296-434)”. In Magic and Ritual in the Ancient World, edited by Paul Mirecki and Marvin Meyer. Leiden – Boston – Köln: Brill, 2002, 344-358. URL

An excellent fuller discussion of the magical assemblage from the Louvre and its implications for our understanding of Graeco-Egyptian magic.

Preisendanz, Karl, and Albert Henrichs. Papyri Graecae Magicae: Die Griechischen Zauberpapyri. 2 Vols. Stuttgart: Teubner, 1973–1974. URL

The most comprehensive editions of the Greek Magical Papyri, containing the Greek texts with German translations. The edition of PGM IV appears from page 64 of volume 1, and the section discussed here (lines 296-466) is edited on pages 82-86.