In Coptic, Christmas is p-houmise m-pe-Khristos (ⲡϩⲟⲩⲙⲓⲥⲉ ⲙⲡⲉⲭⲣⲓⲥⲧⲟⲥ), “Christ’s Birthday”, and in the modern Coptic Orthodox Church it has been celebrated from at least 433 CE on the twenty-ninth of the month of Khoiak. In the old Julian calendar this corresponded to the twenty-fifth of December, but since the calendar reforms of Pope Gregory in 1582, Coptic Christmas corresponds to the seventh of January in the now-dominant Gregorian calendar.

In orthodox Christianity, Christmas represents one of the most important moments in history, when God became man, and was born through a virgin. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there are a few Coptic magical texts that attempt to draw upon the power of this divine paradox.

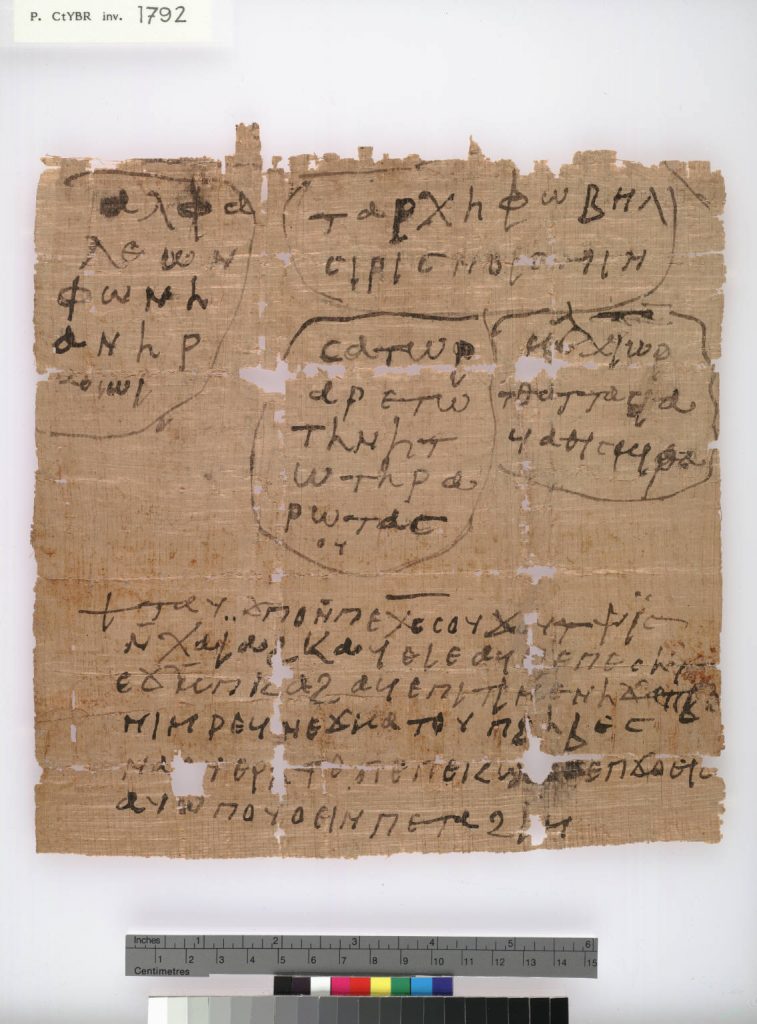

P. CtYBR inv. 1792 is a small sheet of papyrus dated, based on its handwriting, to the late sixth or early seventh century. After it had been written, it was folded several times to form a small square package, which could easily be worn or carried as an amulet.

| S | A | T | O | R |

| A | R | E | P | O |

| T | E | N | E | T |

| O | P | E | R | A |

| R | O | T | A | S |

The sator-square

The upper part contains a series of powerful “magical” sequences, each enclosed in a small circle. In the middle is the sator-square, a palindrome of Latin origin, here written in Greek letters; while its original meaning, if it ever had one, is uncertain, its unusual property is that it yields the same sequence no matter the direction in which it is read – right to left, left to right, up or down. First attested in first century Pompeii, it has a long history in magic, and in the late antique Egyptian context the individual words were sometimes associated with the nails with which Jesus was fixed to the cross.

| A | L | Ph | A |

| L | E | Ô | N |

| Ph | Ô | N | Ê |

| A | N | Ê | R |

The alpha-leôn square

In the top left is another well-known sequence, this time of Greek origin, the alpha-leôn square. The words – “alpha, lion, voice, man” – describe the four living creatures mentioned in the Book of Revelation 4.6-8, understood in Egyptian Christianity as the four cherubim who support the chariot of God.

The last recognisable sequence is in the lower right, and is our first clue that this papyrus has something to do with the Christmas story. It is the names of the three magi who brought the baby Jesus gold, frankincense and myrrh, as preserved in the Coptic tradition – Melchior, Thaddias, and Bethezora. In English, the word magos is often translated as “wise man”, and popular retellings often call them “the three kings”. Scholars still debate what the author of the Gospel of Matthew meant when he used the word magos to describe them, but in Greek and Coptic it is one of the most common words for a “magician”, and so usually has very negative connotations; we hope to discuss this in more detail in a future post. For now, we might wonder if the association of the magi with magic is one of the reasons for the appearance of their names here, alongside the magical squares.

While the lists of circled names in the top part of the papyrus gives the amulet some of its power, the lower part tells us its purpose:

+ Christ was born on the 29th of Khoiak. He came down upon the earth, and he rebuked all of the venomous crawling things. Your word is the lamp of my feet, oh Lord, and the light of my way.

P.CyYBR inv. 1792 ll.1-6

The final part of this section is a quotation from Psalm 118 – one of the more popular psalms in Egyptian amulets – but what interests us here is the first part. The reference to Jesus’ descent to earth – his birth on Christmas Day – is tied here to his role as the saviour of mankind. Several biblical passages (Psalm 90.13, Genesis 3.15) were understood by Christians to refer to Jesus trampling the Devil, who took the form of a snake. In popular Egyptian Christianity, Jesus’ victory over the Old Serpent became his victory over the real venomous and poisonous creatures that threatened their lives – snakes, scorpions, lizards and mosquitos, all captured by the Coptic word jatfe (ϫⲁⲧϥⲉ).

Like many Coptic magical texts, this amulet draws upon many sources for its power: the sator-square, the names of the four living creatures and the three magi, a biblical psalm – but it brings them together with an invocation of that pivotal moment in Christian history, the birth of God as man, in order to protect its wearer from the biting and stinging creatures who were a constant danger in Egypt, even at Christmas.

References and Further Reading

Brashear, William M. “The Coptic Three Wise Men”, Chronique d’Égypte 58 (1983): 297-310.

Discussion of the three magi in the Egyptian religious and magical tradition.

Meyer, Marvin W., and Richard Smith. Ancient Christian Magic: Coptic Texts of Ritual Power. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press, 1999, no. 55, pp. 101-102.

Translation of the text discussed here.

Mihálykó, Ágnes T. “An Egyptian Christmas Carol”, Papyrus Stories: Ancient Lives from the Ancient Past (12th December 2018) [

https://papyrus-stories.com/2018/12/12/an-egyptian-christmas-carol/]

Discussion of the earliest hymns from Egypt

Parássoglou, George M. “A Christian Amulet against Snakebite.” Studia Papyrologica no. 13 (1974): 107–110.

Original publication of the text discussed here.

P.CtYBR inv. 1792 qua [http://findit.library.yale.edu/catalog/digcoll:2759554]

Yale University Collections web page for the text discussed here.

One Comment

Pingback: